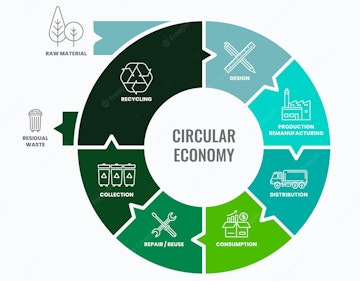

Businesses and governments are preparing to participate in a circular economy, a transformative endeavour with high environmental and economic goals. The circular economy, as we discovered in the article “Circular economy within the nautical industry”, could be implemented in physical vessels in the maritime industry. If you want to learn more about what the circular economy is, we recommend reading up on the article mentioned.

Nevertheless, the transition to a circular economy within the nautical industry has the potential to transform how ships are designed, maintained and recycled, even through to how they are owned and valued. The predicted construction of ships using low-carbon technologies, as well as the growing number of ships headed for the recycling yard, present both opportunity and urgency for circular innovation. Despite the warnings of many political and social scientists, the circular economy will exclude disadvantaged groups and fail to limit global resource use. Instead, they argue that a just transition must be inclusive and fair in order to achieve an ethical and sustainable circular economy.

The demand for zero-carbon emissions gives opportunities to integrate circular technologies into the design of modern ships. According to the Sustainable Shipping Initiative, based on the research of fleet renewal trends, worldwide recycling volumes will more than triple by 2028 and nearly quadruple by 2033.

Beaching

The future of boat recycling may take several forms. Ship recycling systems can be classified based on their environmental sustainability, worker safety, and technological complexity. The "beaching-gravity method" is the least rigorous practice.

This method is widely used in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. It entails manoeuvring ships at full speed against a shore during high tide for subsequent hand-dismantle. Or, to put it another way, the ship is grounded during high tide and demolished on the mudflats at low tide, when it is not buried by the water. While the ship is being cut here, the tide is releasing pollutants into the surrounding area. As a primarily low-cost approach, it has significant negative consequences for human safety and the environment due to uncontrolled carcass decomposition and direct waste emissions into the water. Another recycling process is the "landing method," which is used in Turkey and is more environmentally sound.

Water Jet Cutting Systems

A different way to dismantle a ship could be water jet-cutting. Water jet-cutting uses a tiny diameter nozzle to spray water combined with natural abrasives such as sand. This approach, which may be used for a range of metals including steel, is now the most promising technology for this purpose. Water jet cutting provides environmental benefits while also being cost-effective and maximising material recycling. The finely defined kerf, or cut, generated by the high-pressure water jet saves raw materials, energy, and time because workers only need to pass over the material once. Unlike typical cutting systems, the machinery requires no cooling or lubricating oils, minimising the need to purchase, maintain, and dispose of chemicals.

The Material Passport

A material passport might be useful in understanding and preserving the value of a boat. The material passport, also known as a product passport or circularity passport, is a data collection that describes the properties of the materials and components in a product system that provide them value for current use, recovery, and reuse. This material passport might aid in determining which materials are installed and where on the ship. The developed material passport for the ship might then be used as a material bank. A material bank is a bank where they own the materials used to build a boat. So for example as Prof. Dr. Michael Braungart explains “If there were 3000 tons of copper in a cruise ship, for example, someone else might own that copper, making that copper USD 3 million cheaper to build the ship. A shipowner might pay an interest rate of 3 to 5 percent for the use of the copper over the lifetime of that ship, which would then be reclaimed at end-of-life.” There is still a long way to go before that happens. However, the material passport might be one approach to end the material loop and carry out successful ship recycling in the future. Closing the gap between ship recycling and construction might result in the development of high-quality jobs and a radical change in ship design since the best materials, not the cheapest, can then be used. Furthermore, the preservation of materials and values has the potential to revolutionise material flows and even ship ownership. According to Prof. Dr. Michael Braungart and researcher Kamila Szwejk of Leuphana University Lüneburg (Germany), who are collaborating with Meyer Werft, a German shipbuilder of cruise vessels (for the Carnival corporation, among others), to create a prototype of an entirely 'circular' cruise ship cabin, and said that a ship could become a materials bank, which would allow it to be made much more cost-effectively as well, as extra investors hold more materials. However, so far Braungart and Szweik together with Meyer Werft tried to collect all materials used in a ship's cabin for the first time and demonstrated that third-party opinions began to scrutinise the construction process.

Ship Building Materials

The materials used in the building of recreational vessels vary depending on the shipyard, the manufacturing model (based on demand), performance, activity, navigation conditions, maintenance, and cost. Some boats are built of aluminium because of its robustness and inexpensive maintenance compared to other materials, such as wood, which may be quite expensive to maintain. Steel is the material of choice because of its hardness and low maintenance costs due to oxidation. Fibreglass, on the other hand, is the dominating material in recreational boat construction due to its design flexibility, cheap maintenance costs, and resistance to corrosion and chemicals. Nonetheless, steel, which makes up more than 95% of a vessel's construction, may be recycled endlessly.

The future of materials used in the boat building industry could be flax-based as it is lighter than glass fibre and saves up to 75% of CO2 savings. Additionally, flax grows from seed to crop in eight weeks, rarely needs irrigation, and chemicals are not required. So far, this environmentally friendly product has been used by German yard Greenboats.

However, dangerous elements such as asbestos, naturally existing radioactive material (NORM), and mercury present in ship structures must be removed in order to recover excellent grade scrap steel and safely reuse the raw material.

Looking at the destinations with the most active ship recycling industries, Denmark appears to be one of the most active in all of Europe. Furthermore, Nautiluslog, located in Hamburg, is one of several start-ups that provide digitised solutions to map dangerous compounds on a ship with minimum input from the ship's owners. This service is provided to shipowners by Sea2Cradle, a ship recycling advisory organisation. As Bert van Grieken, commercial director of Sea2Cradle explains, "most shipowners do not invest in having their own people focus on ship recycling because it is not a continuous activity". As Grieken points out, there are still corporations that do not care about ethical ship recycling, but the number of companies that give this matter serious consideration is thankfully growing.

Conclusion

Overall, the boat recycling subject is one in which progress is being made, albeit in small measures. The future process of how a boat is built and recycled is still in its early stages, and it requires greater attention from all stakeholders engaged in the boat and shipping industry.